INTRODUCTION

Multicore processors have opened the door to new levels of performance in embedded applications. To unlock multicore’s full performance potential, advanced programming techniques such as concurrency and parallel computing are necessary. Applications must be designed so that individual portions of a program can be run in parallel on the various processor cores. Thus, while multicore platforms bring breakthrough processing power, they also add complexity, including a new class of particularly pernicious concurrency bugs.

These new bugs, which include race conditions, deadlocks, livelocks, resource starvation, and non-deterministic behavior, are difficult to find when they manifest and even more difficult to diagnose. Concurrency bugs can exhibit unusual symptoms that surface long after the initial events that triggered them, making them particularly tricky, and in addition, they are frequently very hard to reproduce. Reducing the risks of concurrency bugs, therefore, requires a multifaceted approach that includes peer code reviews, advanced static analysis, and testing.

Advanced static analysis solutions have been available to address concurrency problems for C and C++ programs. But until now, the industry has lacked a comprehensive static analysis solution that addresses concurrency problems that are specific to Java programs. Java is increasingly popular with embedded developers, and with 28% of them using Java today, it is now the third most popular language for embedded systems, after C and C++.

Cutting-edge academic research into software concurrency behavior at Edinburgh University led to the development of ThreadSafe, the industry’s most sophisticated static analysis tool targeting concurrency behavior in Java programs. GrammaTech, whose CodeSonar suite of program analysis tools already includes the most advanced static analysis for C and C++, and interoperability with FindBugs and PMD open-source tools for Java, now includes ThreadSafe as a fully integrated plug-in to CodeSonar, to offer a comprehensive analysis of Java programs.

ADVANTAGES OF JAVA

Java, the world’s most popular programming language, is a high-level language designed to be reliable, secure, platform-independent, and easy to learn. Widely used in enterprise and server applications, Java is also a good choice for embedded systems, where it is frequently used for system-control functions and user interfaces. With the adoption of multicore architectures and the increased performance and efficiency they bring to embedded platforms, the use of Java on embedded devices is on the rise. One of the fundamental weaknesses of C and C++ languages is that they were not designed for concurrency. In contrast, Java has always had built-in support for multithreading within the programming language syntax, source compilers, and standard libraries. Additionally, Java 5 added the java.util.concurrent library, which was extended in Java 6 and Java 7 to provide extensive support for concurrent and parallel programming.

Still, writing a correct concurrent Java program is notoriously difficult and exponentially harder with the advent of multicore architectures. Past generations of processors relied on incremental increases in processor clock speeds to boost performance. Multicore processors, on the other hand, use parallel processors and higher levels of concurrency to achieve fully-scalable

performance. They also allow the cores

to communicate directly through shared

hardware caches for better performance

and improved resource allocation, which

further adds to programming complexity

(see Figure 1).

Further, since most embedded developers are new to multicore programming models, the risk of introducing concurrency bugs in Java programs is even more significant, and for mission-critical, safety-critical applications, these risks pose a clear and present danger.

MULTITHREADING

Concurrency is the notion of multiple things happening at the same time. In the real world, there are always many things happening at once, and humans address this by multitasking. We start a task, and, before finishing it, begin the next. We switch back and forth, working on multiple tasks concurrently. When computers multitask, they do so by multithreading. An application is broken into multiple threads that can be run concurrently, i.e. in overlapping intervals of time. Multithreading is used in both single-processor and multiprocessor/multicore environments and serves two distinct purposes: concurrency and parallelism.

In the case of single processor systems, for example, threads are used to enable asynchronous handling of interactions with other software and the real world concurrently. In multicore systems, threads serve the additional purpose of allowing portions of the software, i.e. threads, to run in parallel across the various processor cores.

A great deal of multithreaded code existed before the introduction of multicore processors; however, if a multithreaded program runs properly in a single processor system, there is no guarantee that concurrency bugs will not occur when the program runs on a multicore processor.

INTERLEAVING

Interleaving is one of the greatest strengths of concurrency, but it is also the main source of its problems. Interleaving means that each time a thread runs, the order in which instructions are executed varies depending on what other threads are running at the same time. When programs are properly written, interleaving can improve performance, but if bugs are introduced through programming errors, interleaving can lead to unpredictable results.

The number of possible interleavings increases enormously as the number of instructions grows, a phenomenon known as a combinatorial explosion. Even the smallest threads have many possible interleavings. Real-world concurrent programs have astronomical numbers of legal interleavings, so testing every interleaving is infeasible. Likewise, it is impossible to explore every potential execution path using peer code reviews or walkthroughs. This is where advanced static analysis tools excel.

RACE CONDITIONS

One of the most common unintended consequences of thread interleaving is the race condition, a class of problems that do not even exist in a single-threaded world. A race condition is any situation in which the combined outcome of two or more threads of execution varies, depending on the precise order in which the interleaved instructions of each are executed. This happens when multiple threads access a shared piece of data, with at least one of them changing its value without an explicit synchronization peration to coordinate the accesses. Depending on the thread interleaving, the system can be left in an inconsistent state.

A simple example of a race condition is a manufacturing assembly line that maintains a running count of items completed with separate controllers responsible for counting each kind of object. In a multithreaded system, a race condition can arise because the controllers read and write a shared piece of data: the count. If two different types of items, for example, items A and B, are completed at the same time, the controllers for A and B may both read the same starting counter value C, and write the same updated value C+1, when in fact the correct final value should be C+1+1. Many interleavings result in correct counts, but in cases where they do not, the consequences can be critical (see Figure 3 below).

DEADLOCKS, LIVELOCKS, AND STARVATION

In order to protect shared resources and eliminate race conditions, a number of techniques are available, for example, synchronizing via locks. These techniques can introduce problems of their own, however, including performance bottlenecks and increased code complexity. Worse, they can introduce problems such as deadlocks, livelocks, and starvation.

In a deadlock, two or more threads prevent each other from making progress by each holding a lock needed by the other. Consider, for example, multiple assembly lines that share a count value of the total number of items currently under assembly, and a second bad_items value that records how many finished items have failed quality control. One thread acquires the lock on the count, another acquires the lock on bad_items. Now, neither thread can obtain the second lock it needs, so neither can carry out its operations or get to the point where it will release its lock. Both threads are completely stuck and unable to complete their updates (see Figure 4).

While much less common than deadlocks, both livelocks and starvation are problems that every designer of concurrent software is likely to encounter. A livelock is similar to a deadlock, except in a livelock the threads are not blocked, but instead simply too busy responding to each other to resume work. The classic real-world example of livelock occurs when two people meet in a narrow corridor and try to pass each other, but both move in the same direction at the same time, thus continuing to block each other.

In starvation, threads are said to starve when they are left waiting for a lock that is held by another thread for a very long time. If the thread hogging the lock is invoked very frequently, other threads needing the lock will starve.

HOW STATIC ANALYSIS WORKS

Advanced static analysis tools use symbolic execution engines to identify potential problems in a program without actually having to run the program. They work much like compilers, taking source code as input, then parsing it and converting it to an Intermediate Representation (IR). Whereas a compiler would use the IR to generate object code, static analysis tools retain the IR, also called the model.

Checkers perform analysis of the code to find common defects, violations of policies, etc. Checkers operate by traversing or querying the model, looking for particular properties or patterns that indicate defects. Sophisticated symbolic execution techniques explore paths through a control-flow graph, which is a data structure representing all paths that might be traversed through a program during its execution.

Algorithms keep track of the abstract state of the program and know how to use that state to exclude consideration of infeasible paths. The depth of the model determines the effectiveness of the tool. That depth is based on how much knowledge of program behavior is built-in, how much of the program it can take into account at once, and how accurately it reflects actual program behavior (see Figure 5 below).

OPEN SOURCE TOOLS

Many developers take advantage of popular open-source tools, including FindBugs, PMD, and CheckStyle, to find bugs in Java. The most widely used of these, FindBugs, uses static analysis to identify hundreds of different types of potential errors in Java programs. FindBugs operates on Java bytecode, the form of instructions that the Java virtual machine executes. Both PMD and CheckStyle detect bad practices and check the code for adherence to coding standards.

Each of these tools has its strengths. An important advantage of static analysis tools, in general, is that they can be used early in development to find bugs even before testing begins. Most of the static analysis tools available for Java are general-purpose and catch a range of surface-level problems that are valuable to be found early in development.

THREADSAFE TARGETS CONCURRENCY BUGS

In contrast to the open source tools described above, ThreadSafe is tailored for the very precise identification of concurrency problems in Java. It uses advanced static analysis of source code with whole program interprocedural analysis. Due to the depth of its model, ThreadSafe is able to find concurrency problems that are missed by other tools.

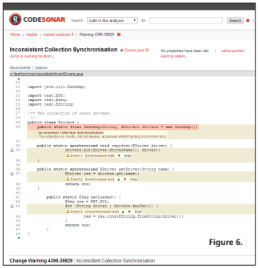

ThreadSafe identifies a wide variety of application risks and security vulnerabilities. In addition to identifying race conditions and deadlocks, ThreadSafe can pinpoint unpredictable results caused by incorrect use of the concurrent collection libraries provided by java.util.concurrent, bad error handling, or incorrect synchronization when coordinating access to shared non-concurrent collections. It can also help diagnose performance bottlenecks caused by incorrect API usage, redundant synchronization, and unnecessary use of a shared mutable state.

A good framework can help a programmer build safe concurrent applications. ThreadSafe incorporates an understanding of Java libraries and frameworks that have concurrent behavior and multiple code entry points, including the standard java.util.concurrent library and also the Android framework for mobile applications.

ThreadSafe enables developers to discover the underlying design intentions of existing concurrent code, and recognize when new code deviates from this design. It provides early warnings when new concurrency defects are first introduced, and, when integrated with CodeSonar’s work-flow management and additional group development features, provides developers with a powerful ability to identify and understand them.

INTEGRATED SOLUTION

GrammaTech’s CodeSonar offers the industry’s deepest source code analysis and provides developers a unified interface for analyzing C, C++, and Java source code. CodeSonar’s rich development environment includes automated workflow and powerful tools for program analysis, program inspection, program understanding, and architecture visualization that can be used for both embedded and hosted platforms.

CodeSonar provides an infrastructure for managing the results of static analysis and is designed for groups of people to collaborate at managing and acting on those results effectively. For example, when defects are found, developers can attach an annotation to a specific warning that is visible to other team members who are on the system. The annotation – such as a note, property, or assignment of an action to an individual – will help to manage work and allow users to clearly see how the set of warnings is changing over time.

Warnings can also be superimposed on CodeSonar’s powerful call graph visualization, for an easy understanding of where problems are originating within the whole system. Warnings can also be charted to help identify the riskiest modules. This rich collaborative infrastructure helps teams avoid duplication of effort and helps improve the overall productivity of a team working on complex code.

When used in conjunction with other code quality practices such as code reviews and integration testing, GrammaTech’s CodeSonar with ThreadSafe can significantly reduce the risk of field failures due to undiscovered concurrency bugs in deployed applications. To learn more about CodeSonar, and for a free trial, contact GrammaTech.

REFERENCES:

- Anderson, Paul. “Finding Concurrency Errors with GrammaTech Static Analysis.” GrammaTech. GrammaTech, n.d. Web. 19 Dec. 2013. <https://codesecure.com/resources/whitepapers>.

- Atkey, Robert. “Maintaining Safe Concurrent Code with ThreadSafe.” Contemplateltd.com. Contemplate, n.d. Web. 12 Dec. 2013. <http://www.contemplateltd.com/threadsafe/maintaining-safe-concurrent-code-with-threadsafe>.

- Sannella, Don. “Testing Just Isn’t Good Enough Anymore.” Contemplateltd.com. Contemplate, n.d. Web. 12 Dec. 2013. <http://www.contemplateltd.com/threadsafe/testing-just-isnt-good-enough-anymore>.

- Ylvisaker, Ben. “Multi-Core Processors Are a Headache for Multithreaded Code.” Web log post. GrammaTech.com. GrammaTech, 17 Apr. 2013. Web. 19 Dec. 2013. <https://codesecure.com/blog/multi-core-processors-headache-for-multithreaded-code>.

- McCabe, Zach D. “On Target: Embedded Systems.” Web log post. On Target: Embedded Systems. VDC Research, 23 Aug. 2013. Web. 19 Dec. 2013. <http://blog.vdcresearch.com/embedded_sw/2013/08/a-turbo-shot-of-java.html>.